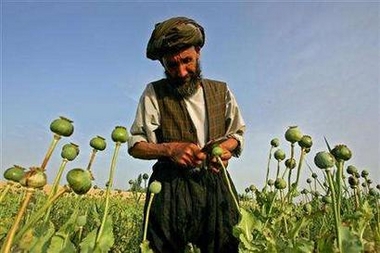

US Occupied Afghanisatn Moves Poppy Production To Record Highs

LASHKAR GAH, Afghanistan – Afghanistan produced record levels of opium in 2007 for the second straight year, led by a staggering 45 percent increase in the areas the US and Nato have the most concentration, Helmand Province, according to a new United Nations survey to be released Monday.

The report is likely to touch off renewed debate about the United States’ $600 million counternarcotics program in Afghanistan, which has been hampered by security challenges and endemic corruption within the Afghan government, occupiers and natives.

“I think it is safe to say that we should be looking for a new strategy,” said William B. Wood, the American ambassador to Afghanistan, commenting on the report’s overall findings. “And I think that we are finding one.”

Mr. Wood said the current American programs for eradication, interdiction and alternative livelihoods should be intensified, the funding should be increased, but he added that ground spraying poppy crops with herbicide remained “a possibility.” Afghan and British officials have opposed spraying, saying it would drive farmers into the arms of the Taliban.

While the report found that opium production dropped in northern Afghanistan, Western officials familiar with the assessment said, cultivation rose in the south, where Taliban insurgents urge farmers to grow poppies.

Although common farmers make comparatively little from the trade, opium is a major source of financing for the Taliban, who gain public support by protecting farmers’ fields from eradication, according to American officials. They also receive a cut of the trade from traffickers they protect.

In Taliban-controlled areas, traffickers have opened more labs that process raw opium into heroin, vastly increasing its value. The number of drug labs in Helmand rose to roughly 50 from 30 the year before, and about 16 metric tons of chemicals used in heroin production have been confiscated this year.

The Western officials said countrywide production had increased from 2006 to 2007, but they did not know the final United Nations figure. They estimated a countrywide increase of 10 to 30 percent.

The new survey showed positive signs as well, officials said.

The sharp drop in poppy production in the north is likely to make this year’s countrywide increase smaller than the growth in 2006. Last year, a 160 percent increase in Helmand’s opium crop fueled a 50 percent nationwide increase. Afghanistan produced a record 6,100 metric tons of opium poppies last year, 92 percent of the world’s supply.

Here in Helmand, the breadth of the poppy trade is staggering. A sparsely populated desert province twice the size of Maryland, Helmand produces more narcotics than any country on earth, including Myanmar, Morocco and Colombia. Rampant poverty, corruption among local officials, a Taliban resurgence and spreading lawlessness have turned the province into a narcotics juggernaut.

Poppy prices that are 10 times higher than those for wheat have so warped the local economy that some farmhands refused to take jobs harvesting legal crops this year, local farmers said. And farmers dismiss the threat of eradication, arguing that so many local officials are involved in the poppy trade that a significant clearing of crops will never be done.

American and British officials say they have a long-term strategy to curb poppy production. About 7,000 British troops and Afghan security forces are gradually extending the government’s authority in some areas, they said. The British government is spending $60 million to promote legal crops in the province, and the United States Agency for International Development is mounting a $160 million alternative livelihoods program across southern Afghanistan, most of it in Helmand.

Loren Stoddard, director of the aid agency’s agriculture program in Afghanistan, cited American-financed agricultural fairs, the introduction of high-paying legal crops and the planned construction of a new industrial park and airport as evidence that alternatives were being created.

Mr. Stoddard, who helped Wal-Mart move into Central America in his previous posting, predicted that poppy production had become so prolific that the opium market was flooded and prices were starting to drop. “It seems likely they’ll have a rough year this year,” he said, referring to the poppy farmers. “Labor prices are up and poppy prices are down. I think they’re going to be looking for new things.”

On Wednesday, Mr. Stoddard and Rory Donohoe, the director of the American development agency’s Alternative Livelihoods program in southern Afghanistan, attended the first “Helmand Agricultural Festival.” The $300,000 American-financed gathering in Lashkar Gah was an odd cross between a Midwestern county fair and a Central Asian bazaar, devised to show Afghans an alternative to poppies.

Under a scorching sun, thousands of Afghan men meandered among booths describing fish farms, the dairy business and drip-irrigation systems. A generator, cow and goat were raffled off. Wizened elders sat on carpets and sipped green tea. Some wealthy farmers seemed interested. Others seemed keen to attend what they saw as a picnic.

When Mr. Stoddard and Mr. Donohoe arrived, they walked through the festival surrounded by a three-man British and Australian security team armed with assault rifles. “Who won the cow? Who won the cow?” shouted Mr. Stoddard, 38, a burly former food broker from Provo, Utah. “Was it a girl or a guy?”

After Afghans began dancing to traditional drum and flute music, Mr. Donohoe, 29, from San Francisco, briefly joined them.

Some Afghans praised the fair’s alternatives crops. Others said only the rich could afford them. Haji Abdul Gafar, 28, a wealthy landowner, expressed interest in some of the new ideas.

Saber Gul, a 40-year-old laborer, said he was too poor to take advantage. “For those who have livestock and land, they can,” he said. “For us, the poor people, there is nothing.”

Local officials said all the development programs would fail without improved security.

Assadullah Wafa, Helmand’s governor, said four of Helmand’s 13 districts were under Taliban control. Other officials put the number at six.

Mr. Wafa, who eradicated far fewer acres than the governor of neighboring Kandahar Province, promised to improve eradication in Helmand next year. He also called for Western countries to decrease the demand for heroin.

“The world is focusing on the production side, not the buying side,” he said.

The day after the agricultural fair, Mr. Stoddard and Mr. Donohoe gave a tour of a $3 million American project to clear a former Soviet airbase on the outskirts of town and turn it into an industrial park and civilian airport.

Standing near rusting Soviet fuel tanks, the two men described how pomegranates, a delicacy in Helmand for centuries, would be flown out to growing markets in India and Dubai. Animal feed would be produced from a local mill, marble cut and polished for construction.

“Once we get this air cargo thing going,” Mr. Stoddard said, “it will open up the whole south.”

That afternoon, they showed off a pilot program for growing chili peppers on contract for a company in Dubai. “These kinds of partnerships with private companies are what we want here,” said Mr. Donohoe, who has a Master’s in Business Administration from Georgetown University. “We’ll let the market drive it.”

As the Americans toured the farm, they were guarded by eight Afghans and three British and Australian guards. The farm itself had received guards after local villagers began sneaking in at night and stealing produce. Twenty-four hours a day, 24 Afghan men with assault rifles staff six guard posts that ring the farm, safeguarding chili peppers and other produce.

“Some people would say that security is so bad that you can’t do anything,” Mr. Donohoe said. “But we do it.”

Mr. Wafa, though, called the American reconstruction effort too small and “low quality.”

“There is a proverb in Afghanistan,” he said. “By one flower we cannot mark spring.”

Source: New York Times (NY)